In our previous blog, Mastering SQL Basics: Part 1, we built a solid foundation—learning how to create databases, define and manage tables, insert and retrieve data, and apply essential SQL commands. Now, equipped with those basics, it’s time to move beyond single-table queries to one of the most critical topics in relational databases: SQL JOINS.

In this post, we’ll continue exactly where we left off. Using the TeamMembers and ClientAccounts tables built in Part 1, you’ll unlock the power of SQL JOINs and learn how to answer complex reporting questions. For richer scenarios, we’ll introduce a new Transactions table, and every example uses the same sample data so you never lose your place.

Before You Begin:

To follow along with this post, you’ll need our TeamMembers and ClientAccounts tables set up.

Option 1 (Recommended): If you haven’t completed Part 1, please go back to Mastering SQL Basics: Part 1 and follow the instructions to create and populate these tables.

Option 2 (Quick Setup): If you want to jump straight into joins, here are the CREATE TABLE and INSERT statements to quickly set up the necessary tables and initial data.

-- Create the TeamMembers table

CREATE TABLE TeamMembers (

member_id INT NOT NULL,

member_name VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL,

location_city VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL,

commission_rate DECIMAL(4,2) NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (member_id) -- member_id is the unique identifier for each team member

);

-- Create the ClientAccounts table

CREATE TABLE ClientAccounts (

client_id INT NOT NULL,

client_name VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL,

client_city VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL,

satisfaction_rating INT NOT NULL,

assigned_member_id INT NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (client_id), -- client_id is the unique identifier for each client

FOREIGN KEY (assigned_member_id) REFERENCES TeamMembers(member_id) -- Links to TeamMembers table

);

-- Insert initial data into TeamMembers

INSERT INTO TeamMembers VALUES

(101, 'Alice Smith', 'London', 0.12),

(102, 'Bob Johnson', 'San Jose', 0.13),

(104, 'Charlie Brown', 'London', 0.11),

(107, 'David Lee', 'Barcelona', 0.15),

(103, 'Eve Davis', 'New York', 0.10),

(105, 'Fran White', 'London', 0.26);

-- Insert initial data into ClientAccounts

INSERT INTO ClientAccounts VALUES

(2001, 'Hoffman Corp', 'London', 100, 101),

(2002, 'Giovanni Ltd', 'Rome', 200, 103),

(2003, 'Liu Enterprises', 'San Jose', 200, 102),

(2004, 'Grass Solutions', 'Berlin', 300, 102),

(2006, 'Clemens Inc', 'London', 100, 101),

(2008, 'Cisneros Group', 'San Jose', 300, 107),

(2007, 'Pereira Services', 'Rome', 100, 104);

Additionally, create one more table with the records as guided below –

-- Create the Transactions table

CREATE TABLE Transactions (

transaction_id INT NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

amt DECIMAL(7,2) NOT NULL,

odate DATE NOT NULL,

cnum INT NOT NULL,

FOREIGN KEY (cnum) REFERENCES ClientAccounts(client_id)

);

-- Insert initial data into Transactions

INSERT INTO Transactions VALUES (3001, 18.69, '1996-03-10', 2008),

(3003, 767.19, '1996-03-10', 2001),

(3002, 1900.19,'1996-03-10', 2007),

(3005, 5160.45,'1996-03-10', 2003),

(3006, 1098.16,'1996-03-10', 2008),

(3009, 1713.23,'1996-04-10', 2002),

(3007, 75.75, '1996-04-10', 2002),

(3008, 4723.00,'1996-05-10', 2006),

(3010, 1309.95,'1996-06-10', 2004),

(3011, 9891.88,'1996-06-10', 2006);This post will show you how to combine data across tables using JOINS, why this ability is crucial, and provide real-world examples inspired by hands-on learning and classic SQL exercises.

Why Not Put Everything in One Big Table? (A Real-World Analogy)

Imagine running a consulting firm with a single spreadsheet that tracks every staff member, client, and order. Each row needs to include:

- Team member’s name and info

- Client’s details

- Every order’s specifics

You’ll quickly face problems:

- Redundancy: If Alice manages five clients, her name and info are repeated five times.

- Data anomalies: If Alice’s phone number changes, you must update it in every row—miss one, and your records are inconsistent.

- Scalability pain: As your business grows, the table gets unwieldy and error-prone.

- Limited insight: Tracking relationships (like “who manages which clients?” or “which orders belong to which client?”) becomes a headache.

Relational database design solves all this by splitting information into logical tables—staff, clients, orders—each with a unique ID. JOINS are how you bring the pieces together.

What Are SQL JOINS? (And Why They Matter)

A JOIN in SQL is a command that combines rows from two or more tables, based on a related column (usually a key, like an ID). A SQL JOIN allows you to retrieve related information stored in different tables, piecing together a more complete picture from your data. Modern business databases are always relational—customers, orders, staff, and transactions are split across logical tables for consistency and efficiency. JOINS are the glue that reunites this distributed data for meaningful analysis.

Why are joins essential?

- Enables unified reports and complex analytics.

- Promotes normalized, maintainable database designs (each table focuses on one entity).

- Essential for real-world business queries and applications as make queries scalable and maintainable.

Exploring Major SQL Joins

Let’s dive into the core types of SQL joins, referencing practical examples inspired by both classic exercises and common business data structures.

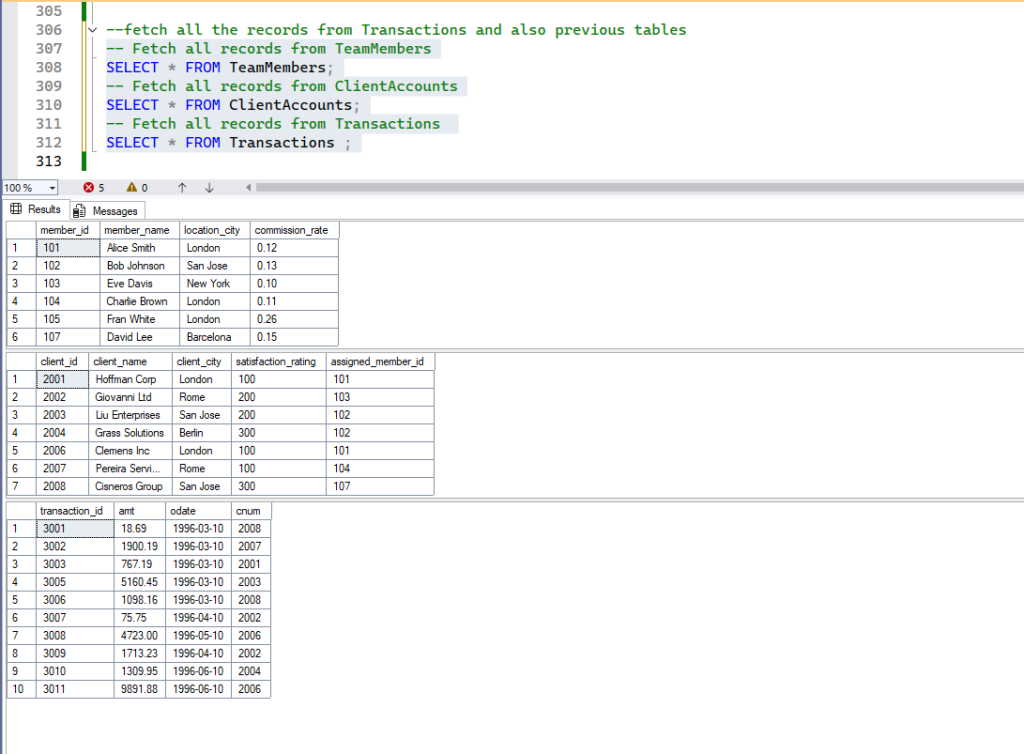

Viewing Our Tables

Before we proceed, let’s look at the current state of our tables with the initial data:

-- Fetch all records from TeamMembers

SELECT * FROM TeamMembers;

-- Fetch all records from ClientAccounts

SELECT * FROM ClientAccounts;

-- Fetch all records from Transactions

SELECT * FROM Transactions ;Run this queries and you will see –

INNER JOIN

- Purpose: Returns only those records where there is a match in both tables.

- When to use: You want to see only data that exists in both tables (for example, clients who are assigned a team member).

- Syntax

-- SQL: INNER JOIN Basic Syntax

SELECT columns -- Select desired columns from both tables

FROM table1 -- The first table

INNER JOIN table2 -- Join with the second table

ON table1.key = table2.related_key; -- Condition to match rows based on common columnsExample 1:

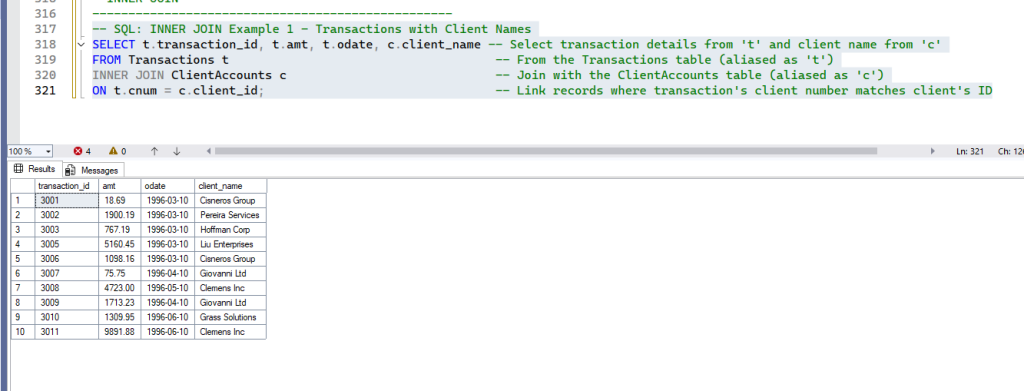

Problem: List all transactions with client name.

-- SQL: INNER JOIN Example 1 - Transactions with Client Names

SELECT t.transaction_id, t.amt, t.odate, c.client_name -- Select transaction details from 't' and client name from 'c'

FROM Transactions t -- From the Transactions table (aliased as 't')

INNER JOIN ClientAccounts c -- Join with the ClientAccounts table (aliased as 'c')

ON t.cnum = c.client_id; -- Link records where transaction's client number matches client's IDExpected result: Expected result: Shows every transaction, with the name of the client placing it. All clients in ClientAccounts currently have transactions, so every transaction finds a matching client.

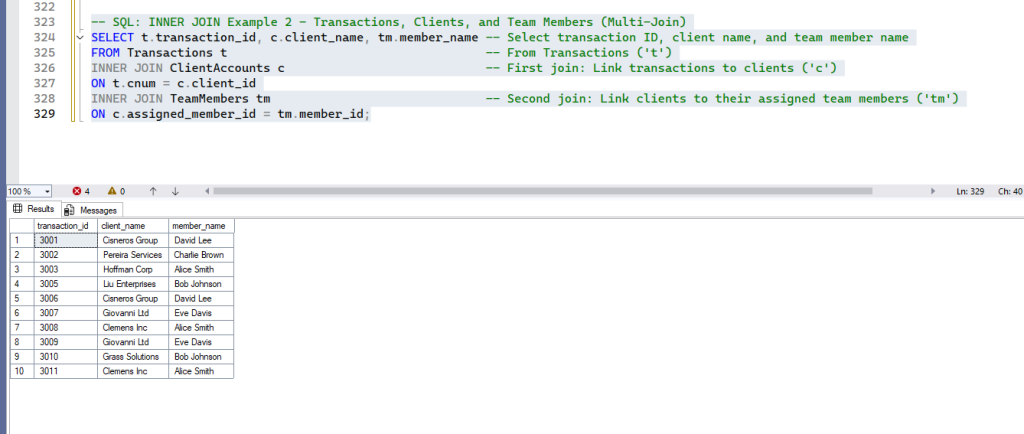

Example 2:

Problem: Show each transaction, the client, and their assigned manager’s name.

-- SQL: INNER JOIN Example 2 - Transactions, Clients, and Team Members (Multi-Join)

SELECT t.transaction_id, c.client_name, tm.member_name -- Select transaction ID, client name, and team member name

FROM Transactions t -- From Transactions ('t')

INNER JOIN ClientAccounts c -- First join: Link transactions to clients ('c')

ON t.cnum = c.client_id

INNER JOIN TeamMembers tm -- Second join: Link clients to their assigned team members ('tm')

ON c.assigned_member_id = tm.member_id;Expected result: All transactions, showing both the customer and which team member they’re assigned to.

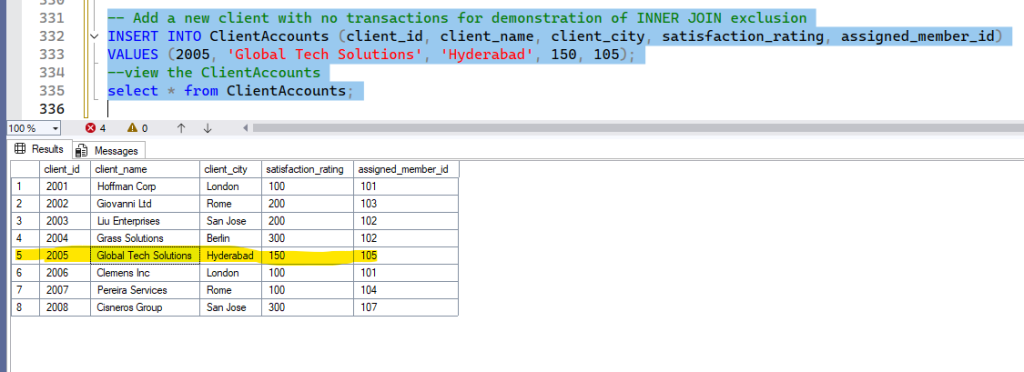

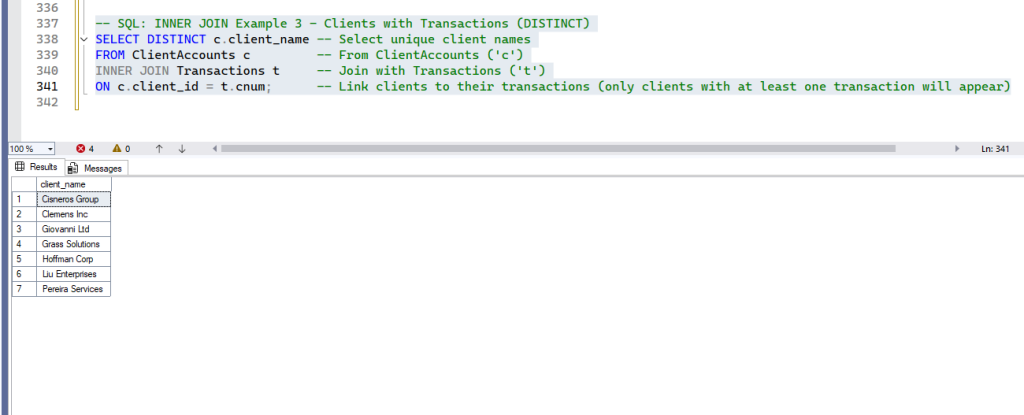

Example 3:

Problem: Clients Having at Least One Transaction

To clearly show what INNER JOIN excludes, let’s add a new client to ClientAccounts that does not have any transactions in the Transactions table. This will make the difference very visible.

-- Add a new client with no transactions for demonstration of INNER JOIN exclusion

INSERT INTO ClientAccounts (client_id, client_name, client_city, satisfaction_rating, assigned_member_id)

VALUES (2005, 'Global Tech Solutions', 'Hyderabad', 150, 105);

--view the ClientAccounts

select * from ClientAccounts;

When executed, you can see new record inserted into the ClientAccounts.

Now, let’s run the INNER JOIN query

-- SQL: INNER JOIN Example 3 - Clients with Transactions (DISTINCT)

SELECT DISTINCT c.client_name -- Select unique client names

FROM ClientAccounts c -- From ClientAccounts ('c')

INNER JOIN Transactions t -- Join with Transactions ('t')

ON c.client_id = t.cnum; -- Link clients to their transactions (only clients with at least one transaction will appear)Expected result: Lists every client with at least one transaction. Notice that ‘Global Tech Solutions’ is explicitly excluded from this list because it has no matching transactions. This clearly shows what INNER JOIN filters out: records that don’t have a match in both tables.

INNER JOIN makes it easy to see only the records that are present in both tables—perfect for finding all transactions tied to a real client or every client that’s managed by a specific team member. Now, let’s take this logic further—with LEFT, RIGHT, and FULL JOINs—to ensure no important data slips through the cracks, including records that don’t have matches in the other table.

LEFT OUTER JOIN (LEFT JOIN)

- Purpose: Returns all records from the left table, plus any matched records from the right; if there’s no match, shows NULL for right table columns.

- When to use: You want to see everything from the first table, and data from the second where available (for example, all employees, whether or not they have clients).

- Syntax

-- SQL: LEFT JOIN Basic Syntax

SELECT columns -- Select desired columns

FROM table1 -- The left table (all its rows will be included)

LEFT JOIN table2 -- Join with the right table

ON table1.key = table2.related_key; -- Condition to match rows. Unmatched rows from table1 will keep their data,

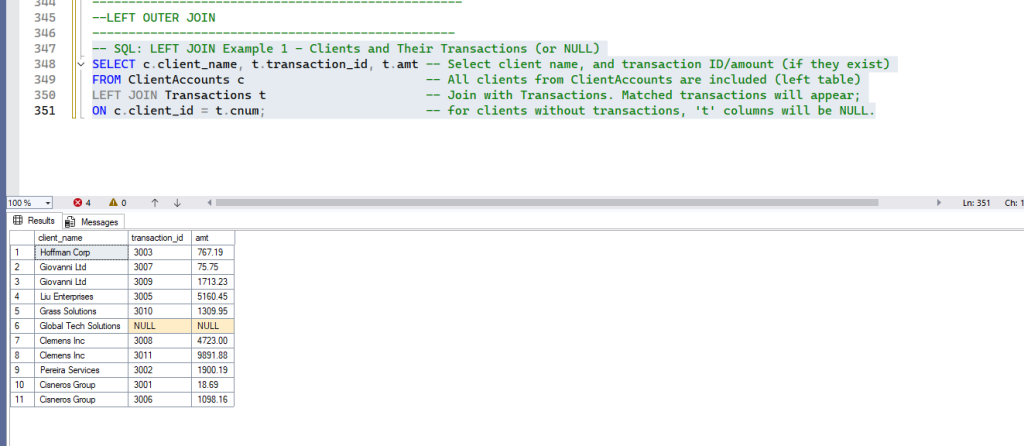

-- with NULLs for table2's columns.Example 1:

Problem: All Clients and Their Transactions (if any)

-- SQL: LEFT JOIN Example 1 - Clients and Their Transactions (or NULL)

SELECT c.client_name, t.transaction_id, t.amt -- Select client name, and transaction ID/amount (if they exist)

FROM ClientAccounts c -- All clients from ClientAccounts are included (left table)

LEFT JOIN Transactions t -- Join with Transactions. Matched transactions will appear;

ON c.client_id = t.cnum; -- for clients without transactions, 't' columns will be NULL.Expected result: All clients listed. Crucially, ‘Global Tech Solutions’ (client_id 2005) is now included, with NULL values for transaction_id and amt, clearly showing that it has no transactions. This is the core behavior of LEFT JOIN – it preserves all records from the left table.

Example 2:

Problem: All Team Members and Their Assigned Clients (if any)

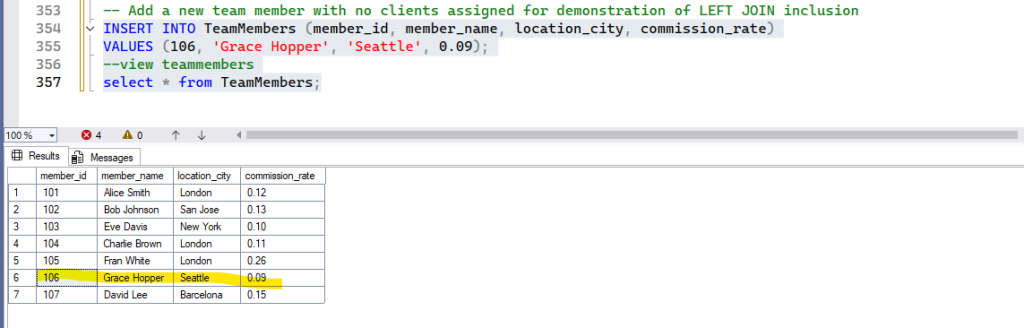

To demonstrate this, let’s add a new team member who is not yet assigned to any client.

-- Add a new team member with no clients assigned for demonstration of LEFT JOIN inclusion

INSERT INTO TeamMembers (member_id, member_name, location_city, commission_rate)

VALUES (106, 'Grace Hopper', 'Seattle', 0.09);

--view TeamMembers

After execution, you can see the new TeamMember added.

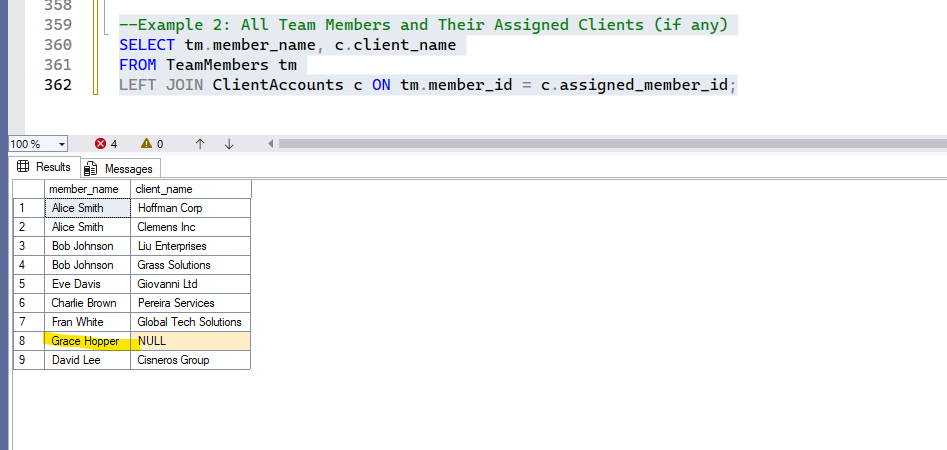

Now, let’s run the LEFT JOIN query:

--Example 2: All Team Members and Their Assigned Clients (if any)

SELECT tm.member_name, c.client_name

FROM TeamMembers tm

LEFT JOIN ClientAccounts c ON tm.member_id = c.assigned_member_id;Expected result: Every team member, with their client(s) if assigned. ‘Grace Hopper’ (member_id 106) is included, showing NULL for client_name, as she is not currently assigned to any client. This highlights how LEFT JOIN ensures all records from the left table (TeamMembers) are present.

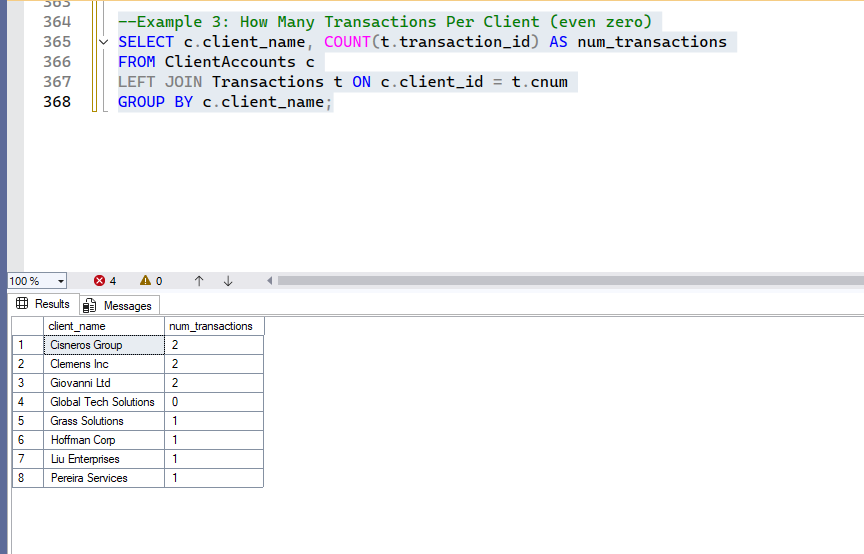

Example 3:

Problem: How Many Transactions Per Client (even zero)

This query is perfect for showing the power of LEFT JOIN combined with aggregation.

--Example 3: How Many Transactions Per Client (even zero)

SELECT c.client_name, COUNT(t.transaction_id) AS num_transactions

FROM ClientAccounts c

LEFT JOIN Transactions t ON c.client_id = t.cnum

GROUP BY c.client_name;Expected result: Each client, and a count of transactions. ‘Global Tech Solutions’ will correctly show a count of 0, demonstrating its lack of transactions, while still being included in the result set.

LEFT JOIN gives you a complete view of every record in your main table—even if it doesn’t have a match on the right. This is invaluable for spotting clients who have never placed a transaction, or team members who aren’t currently managing anyone, highlighting areas that need attention. Up next, see how RIGHT JOIN flips the perspective and makes sure nothing is missed on the other side.

RIGHT OUTER JOIN (RIGHT JOIN)

- Purpose: Returns all records from the right table, plus any matched from the left; if no match, shows NULL for left table columns.

- When to use: You want every record from the second table, such as all clients, even those not assigned to employees.

- Syntax

SELECT columns

FROM table1

RIGHT JOIN table2

ON table1.key = table2.related_key;

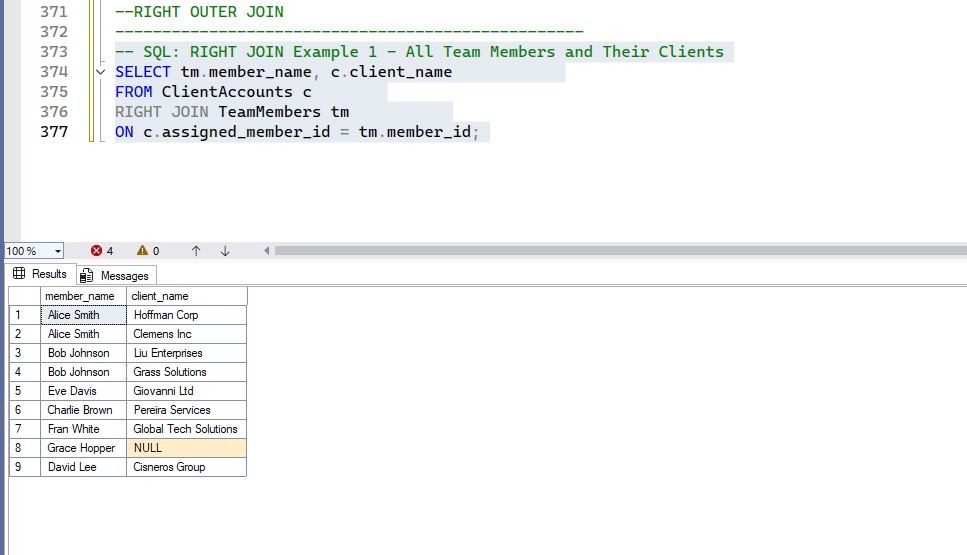

Example 1:

Problem: All Team Members and Their Assigned Clients (including those with no clients)

This example uses ClientAccounts as the left table and TeamMembers as the right table. Since ‘Grace Hopper’ is in TeamMembers but has no matching ClientAccounts, she will appear with NULL client details.

-- SQL: RIGHT JOIN Example 1 - All Team Members and Their Clients

SELECT tm.member_name, c.client_name

FROM ClientAccounts c

RIGHT JOIN TeamMembers tm

ON c.assigned_member_id = tm.member_id; Expected result: All team members listed. ‘Grace Hopper’ (member_id 106) is included, showing NULL for client_name, demonstrating that she has no clients assigned. This is the inverse perspective of a LEFT JOIN from TeamMembers to ClientAccounts.

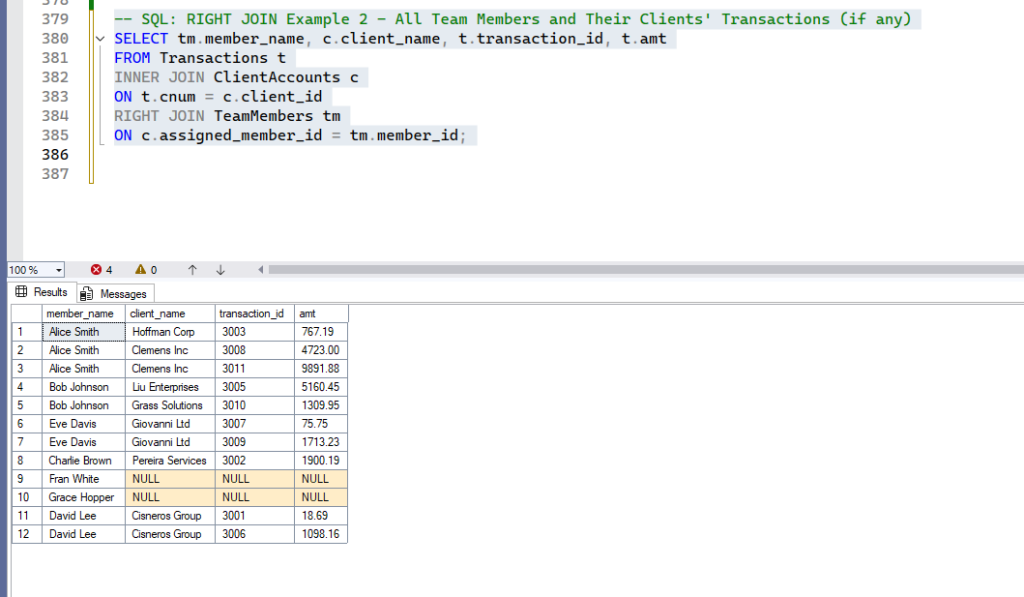

Example 2:

Problem: List all Team Members and any transactions made by clients assigned to them.

This query explicitly shows how RIGHT JOIN ensures all team members are present, even if their assigned clients have no transactions.

-- SQL: RIGHT JOIN Example 2 -Transactions and Assigned Team Member (if possible)

SELECT t.transaction_id, t.amt, tm.member_name

FROM Transactions t

RIGHT JOIN ClientAccounts c

ON t.cnum = c.client_id

LEFT JOIN TeamMembers tm

ON c.assigned_member_id = tm.member_id; Expected result: Shows every transaction, with the client’s manager if the client is assigned to anyone. The row for ‘Global Tech Solutions’ (which has no transactions but has a team member) will appear with NULL transaction details and its assigned team member.

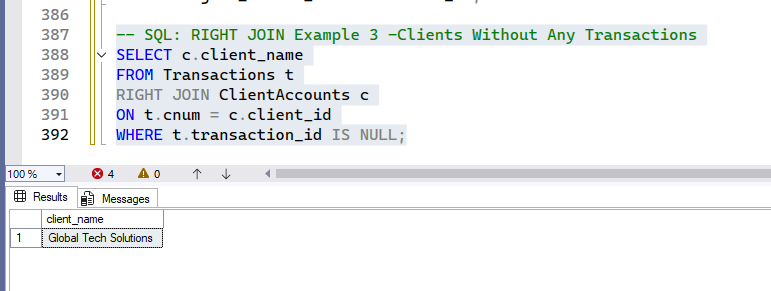

Example 3:

Problem: Clients Without Any Transactions

This query uses RIGHT JOIN to ensure all clients are considered, and then filters to find those without matching transactions.

-- SQL: RIGHT JOIN Example 3 -Clients Without Any Transactions

SELECT c.client_name

FROM Transactions t

RIGHT JOIN ClientAccounts c

ON t.cnum = c.client_id

WHERE t.transaction_id IS NULL;Expected result: Lists all clients who have never made a transaction. ‘Global Tech Solutions’ is the only client returned, as it’s the only one without a matching transaction.

RIGHT JOIN ensures you never overlook data on the right-hand table—displaying all records there, with related info from the left if it exists. It’s especially useful for identifying clients who exist in your system but haven’t yet been assigned to a team member, or transactions that don’t tie back to an established client. Next, we’ll combine both perspectives using a FULL OUTER JOIN for the most comprehensive results.

FULL OUTER JOIN

- Purpose: Combines LEFT and RIGHT JOIN—returns all records from both tables, showing NULLs where there are gaps.

- When to use: You need a complete list showing matches as well as records that exist in only one table.

- Syntax

SELECT columns

FROM table1

FULL OUTER JOIN table2

ON table1.key = table2.related_key;

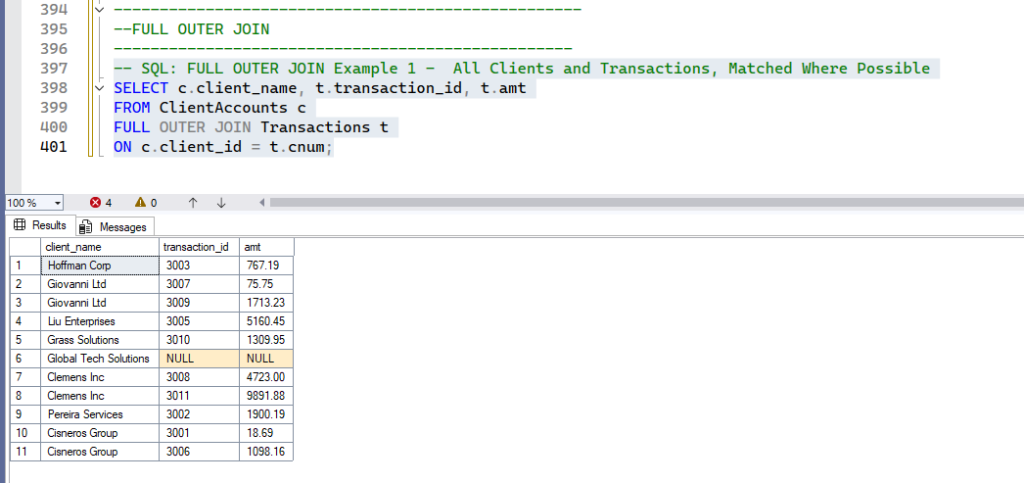

Example 1:

Problem: All Clients and Transactions, Matched Where Possible

-- SQL: FULL OUTER JOIN Example 1 - All Clients and Transactions, Matched Where Possible

SELECT c.client_name, t.transaction_id, t.amt

FROM ClientAccounts c

FULL OUTER JOIN Transactions t

ON c.client_id = t.cnum;Expected result: All transactions and clients, even if no match on the other side. ‘Global Tech Solutions’ appears with NULL transactions, and if there were any transactions without a matching client (which our data prevents due to Foreign Keys), they would also appear with NULL client details.

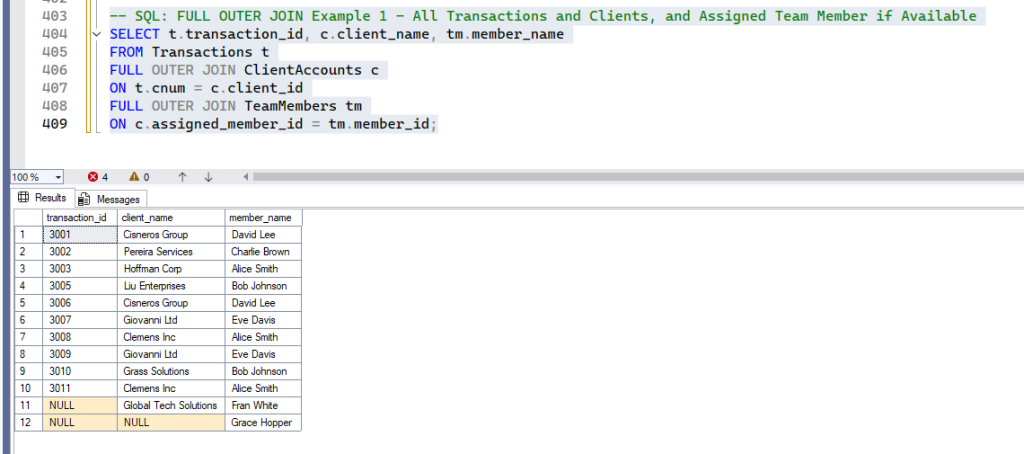

Example 2:

Problem: All Transactions and Clients, and Assigned Team Member if Available

-- SQL: FULL OUTER JOIN Example 1 - All Transactions and Clients, and Assigned Team Member if Available

SELECT t.transaction_id, c.client_name, tm.member_name

FROM Transactions t

FULL OUTER JOIN ClientAccounts c

ON t.cnum = c.client_id

FULL OUTER JOIN TeamMembers tm

ON c.assigned_member_id = tm.member_id;Expected result: All records from all three tables show up, with NULLs for missing links. This complex join demonstrates how FULL OUTER JOIN can reveal all relationships and all “orphan” records across multiple tables. You’ll see Global Tech Solutions (no transaction, but has a team member) and Grace Hopper (no client, no transaction) with appropriate NULLs.

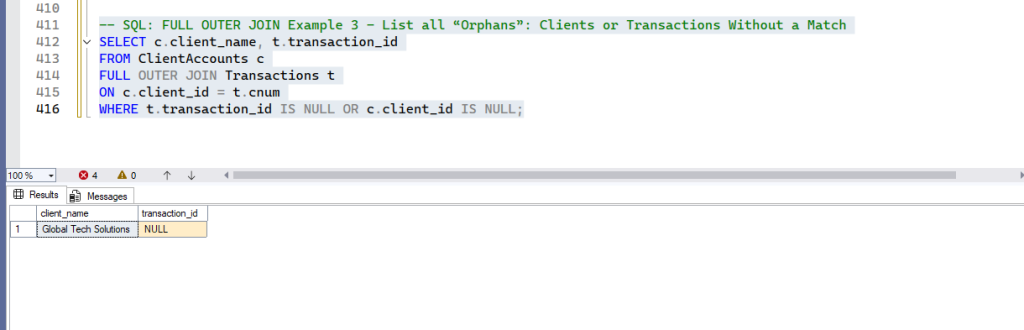

Example 3:

Problem: List all “Orphans”: Clients or Transactions Without a Match

This query specifically filters for records that only exist on one side of the join, effectively finding “orphans.”

-- SQL: FULL OUTER JOIN Example 3 - List all “Orphans”: Clients or Transactions Without a Match

SELECT c.client_name, t.transaction_id

FROM ClientAccounts c

FULL OUTER JOIN Transactions t

ON c.client_id = t.cnum

WHERE t.transaction_id IS NULL OR c.client_id IS NULL;Expected result: Lists all clients with no transactions and all transactions not tied to a valid client (the latter should be rare or impossible with strict FKs). ‘Global Tech Solutions’ is correctly identified here as a client without transactions.

FULL OUTER JOIN pulls everything together—every record from both tables, matched where possible, and NULLs wherever there’s a gap. This offers a true “bird’s-eye view,” showing every relationship and every orphan record in your database, so you’re never in the dark about missing links. You’ll use this for holistic audits and deep data validation.

SELF JOIN

- Purpose: Joins one table to itself. Useful for comparing rows within the same table (such as employees who share a city).

- When to use: For finding relationships inside a single table, such as hierarchies or grouping.

- Syntax

SELECT a.columns, b.columns

FROM table a

JOIN table b

ON a.field = b.field AND a.pk <> b.pk;

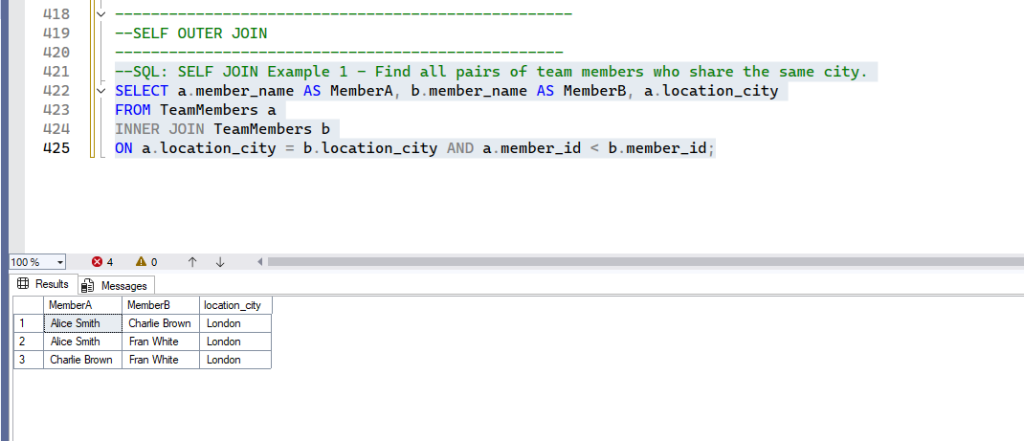

Example 1:

Problem: Find all pairs of team members who share the same city.

--SQL: SELF JOIN Example 1 - Find all pairs of team members who share the same city.

SELECT a.member_name AS MemberA, b.member_name AS MemberB, a.location_city

FROM TeamMembers a

INNER JOIN TeamMembers b

ON a.location_city = b.location_city AND a.member_id < b.member_id;Expected result: All unique pairs of team members based in the same city.

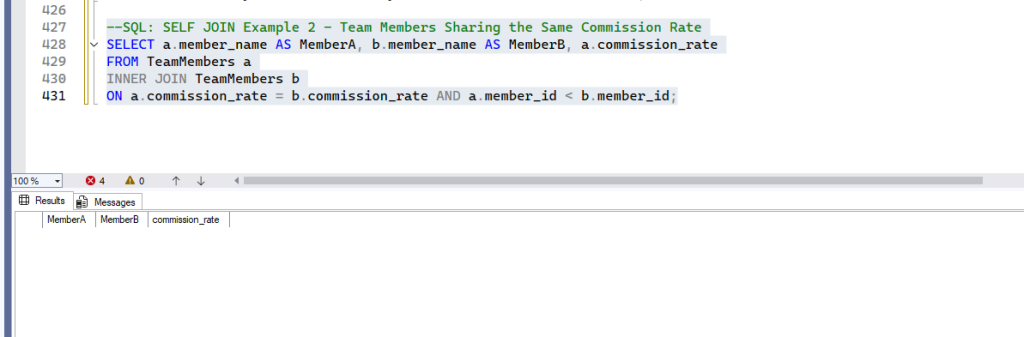

Example 2:

Problem: Team Members Sharing the Same Commission Rate

--SQL: SELF JOIN Example 2 - Team Members Sharing the Same Commission Rate

SELECT a.member_name AS MemberA, b.member_name AS MemberB, a.commission_rate

FROM TeamMembers a

INNER JOIN TeamMembers b

ON a.commission_rate = b.commission_rate AND a.member_id < b.member_id;Expected result: All unique team member pairs with matching commission rates. (Based on the current data, all commission rates are unique, so this query would return no rows. This highlights that a SELF JOIN only returns matches based on the ON condition.)

SELF JOIN opens up intra-table analysis—comparing rows within a single table. Want to find all pairs of team members in the same city, or people sharing a commission rate? With SELF JOIN, you can discover hidden relationships and build team insights that were never possible with single-table logic alone.

Summary Table of JOIN Types

| JOIN Type | Only Matched? | Unmatched from Left? | Unmatched from Right? |

|---|---|---|---|

| INNER JOIN | Yes | No | No |

| LEFT OUTER JOIN | No | Yes | No |

| RIGHT OUTER JOIN | No | No | Yes |

| FULL OUTER JOIN | No | Yes | Yes |

| SELF JOIN | n/a | n/a | n/a |

How Should we Approach JOINS

- Think about the problem statement: Do you want every record, or only those that match?

- Visualize the data: Imagine two lists linked by a common value (like Employee ID or Client ID).

- Identify your keys before you JOIN—usually, it’s an ID shared between tables.

- Start with INNER JOIN to see only records found in both. Use for strict relationships (both sides must exist). Progress to LEFT/RIGHT/FULL joins as you need to handle missing data or unmatched records.

- LEFT/RIGHT JOIN: Reveal missing links or optional relationships.

- FULL JOIN: Best for auditing and ensuring complete coverage.

- SELF JOIN is just joining a table to itself to spot similarities or relationships in a single list.

- Always test joins with sample data—see how results change with NULLs and missing records.

| JOIN Type | Result Set | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| INNER JOIN | Only rows with matches in both tables | Clients with assigned team members |

| LEFT OUTER JOIN | All rows from left + matched/right side or NULLs (if no match) | All employees, even those with no clients |

| RIGHT OUTER JOIN | All rows from right + matched/left side or NULLs (if no match) | All clients, even those not assigned to a team member |

| FULL OUTER JOIN | All rows from both tables, matched or not (NULL for unmatched) | Audit for unmatched orphans; complete reporting |

| SELF JOIN | Rows matched within same table | Employees sharing a city, identifying duplicates, org structure |

Each JOIN type solves a different practical question—understanding their purpose will make reading and writing SQL far easier.

What’s Next? (Forecast: SQL Triggers)

In the next part of this series, we’ll dive into SQL Triggers—automated processes that fire on certain database changes (like INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE). Triggers are essential for enforcing business rules, maintaining audit logs, and crafting smart, reactive databases.

In Summary

- Keeping all data in one table leads to redundancy, inconsistency, and maintenance nightmares.

- Splitting data across logical tables is best practice; JOINS are how you flexibly combine it for analysis.

- Each join type serves real business needs—mastering them is essential for database power users.

- Practice with realistic data and analyze both matched and unmatched scenarios to see the true power of joins.

Keep practicing queries—including edge cases—and get ready for the complex, automated logic of SQL triggers in the forthcoming blog. Happy querying!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.